University of Cuenca, Ecuador.

juanita.argudo@ucuenca.edu.ec

Juanita ARGUDO

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3337-7803.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3337-7803.

University of Cuenca, Ecuador.

juanita.argudo@ucuenca.edu.ec

Mónica ABAD

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8381-5982.

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8381-5982.

University of Cuenca, Ecuador.

monica.abad@ucuenca.edu.ec

Tammy FAJARDO-DACK

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9330-4622.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9330-4622.

University of Cuenca, Ecuador.

tammy.fajardo@ucuenca.edu.ec

Patricio CABRERA

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1741-8804.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1741-8804.

AiA Cia Ltda, Ecuador.

pcabrera.aia@gmail.com

Received: 2018-03-07

Sent for peer review: 2018-05-16

Accepted by peers: 2018-06-16

Approved: 2018-06-18

To reference this article in APA style / Para citar este artículo en APA / Para citar este artigo:

Argudo, J., Abad, M., Fajardo-Dack, T. & Cabrera, P. (2018). Analyzing a pre-service EFL program through the lenses of the CLIL approach at the University of Cuenca-Ecuador. LACLIL, 11(1), 65-86. DOI: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.4

ABSTRACT.

The recent application of Content and Language Integrated Learning programs in higher education provides an extensive area for research due to the quick implementation of English as the medium of instruction for university programs, as well as to the need of university students around the world to communicate through English and to try different learning strategies and methodologies than the ones they used to work with. This study aimed to estimate the extent to which the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) program at the University of Cuenca designed for students who wish to become EFL teachers complies with the principles of the Content and Language Integrated Learning approach. The 121 participants of this study were students from the fourth, fifth, and seventh semesters of the program. A general proficiency English test was administered to these students; some writing assignments to evaluate the development of Higher Order Thinking Skills were considered; and a survey to inquire about students' perceptions on the development of language, content, and Higher Order Thinking Skills in their content subject classes was also applied. The findings revealed that 52% of the students are between A1 and A2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages; this means that they do not have the necessary linguistic conditions to take content subjects. It seems that the parameters teachers used to plan their classes do not consider the three dimensions of this approach (content, language, and procedures); therefore, students are not developing these dimensions simultaneously

Keywords: Content and Language Integrated Learning in higher education; language development; Higher Order Thinking Skills; content understanding; program evaluation.

RESUMEN.

La reciente aplicación de programas de Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenidos y Lenguaje en la educación superior proporciona un área extensa de investigación debido a la rápida implementación del inglés como medio de instrucción para los programas universitarios, así como a la necesidad de que los estudiantes universitarios de todo el mundo se comuniquen en inglés, utilizando metodologías y estrategias de aprendizaje distintas a las que se solían utilizar. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar en qué medida el programa de inglés como lengua extranjera en la Universidad de Cuenca, Ecuador, diseñado para estudiantes que desean convertirse en profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera, cumple con los principios que sustentan el enfoque de aprendizaje integrado de contenido y lenguaje. Los 121 participantes de este estudio fueron los estudiantes de cuarto, quinto y séptimo semestre del programa. A estos estudiantes se les administró una prueba de competencia general de inglés, se consideraron algunas tareas de escritura para evaluar el desarrollo de destrezas de alto nivel de pensamiento, y se aplicó una encuesta para investigar las percepciones de los estudiantes sobre el desarrollo del lenguaje, el contenido y las habilidades de alto nivel de pensamiento en las asignaturas. Los resultados revelaron que el 52 % de los estudiantes están entre A1 y A2 de acuerdo con el Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas; esto significa que no tienen las condiciones lingüísticas necesarias para tomar materias de contenido en una lengua extranjera. Parece que los parámetros que usan los profesores para planificar sus clases no consideran las tres dimensiones de este enfoque (contenido, lenguaje y procedimientos); por lo tanto, los estudiantes no están desarrollando estas dimensiones simultáneamente.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenido y Lenguas Extranjeras en educación superior; desarrollo del lenguaje; destrezas de alto nivel de pensamiento; comprensión del contenido; evaluación del programa.

RESUMO.

A recente aplicação de programas de Aprendizagem Integrada de Conteúdos e Línguas no ensino superior oferece uma extensa área de pesquisa devido à rápida implementação do inglês como um meio de instrução para programas universitários e à necessidade dos estudantes universitários de todo o mundo se comunicarem em inglês, usando metodologias e estratégias de aprendizado diferentes das que costumavam usar. O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar em que medida o programa de inglês como língua estrangeira na Universidade de Cuenca, Equador, projetado para estudantes que querem se tornar em professores de inglês como língua estrangeira, atende aos princípios que apoiam a abordagem de aprendizagem integrada de conteúdo e linguagem. Os 121 participantes deste estudo foram alunos do quarto, quinto e sétimo semestres do programa. Os alunos apresentaram um teste geral de proficiência em inglês, no qual foram consideradas umas tarefas escritas para avaliar o desenvolvimento de habilidades de pensamento de alto nível, e foi feita uma enquete para investigar as percepções dos alunos sobre o desenvolvimento da linguagem, o conteúdo e as habilidades de pensamento de alto nível nas disciplinas. Os resultados revelaram que 52% dos alunos estão entre o nível A1 e A2 de acordo com o Quadro Europeu Comum de Referência para Línguas; isto significa que os estudantes não têm as condições linguísticas necessárias para estudar matérias de conteúdo em uma língua estrangeira. Parece que os parâmetros que os professores usam para planejar suas aulas não consideram as três dimensões dessa abordagem (conteúdo, linguagem e procedimentos); portanto, os alunos não estão desenvolvendo essas dimensões simultaneamente.

Palavras-chave: Aprendizagem Integrada de Conteúdo e Línguas no ensino superior; desenvolvimento da linguagem; Habilidades de Pensamento de Alto Nível; compreensão de conteúdo; avaliação do programa.

Introduction

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is a twofold language educational approach in which "curriculum content is taught through a foreign language, usually to students who participate in some formal education level: primary, secondary or higher" (Dalton-Puffer, 2011, p. 183).

This approach emerged from content-based instruction programs in Canada and North America, and later an immersion program that aimed to promote bilingualism and bilingual literacy in these countries (Dalton-Puffer, 2011). In CLIL classes, students have the opportunity to produce the target language freely, and the topics and materials are presented in an authentic way "since the content has always involved language, and language has always involved content" (Ball, Kelly, & Clegg, 2015, p. 49). Two important fields emerging from CLIL have been reported by Smit and Dafouz (2012):

Integrated Content and Language in Higher Education (ICLHE) and English-Medium Instruction (EMI). Regarding ICLHE the focus is on both, language and content outcomes. Whereas, in EMI the focus is on content and there is not language support. Moreover, EMI is referred only for English teaching while ICLHE for other languages. (p. 8)

The key feature of CLIL is its emphasis on developing content and language simultaneously. As Wolff (2009) pointed out, "experience (of CLIL) shows that both linguistic competence and content learning can be promoted within this integrated concept more effectively than when content and language are taught in isolation" (p. 560). According to Cummins (2013), a well-implemented CLIL program might be effective for learning content and developing language proficiency at the same time, as well as for acquiring strong abilities in the target language. In the same vein, the proficiency hypothesis (Cummins, 1984) suggests that L1 and second language (L2) proficiency can be developed both simultaneously and be mutually beneficial.

The CLIL classroom can be considered a place for the successful development of linguistic and communicative competence of the English language, which, according to Prudnikova (2016) is the ability to think and speak independently, applying available resources to create reliable ideas and conclusions. Presenting your ideas competently relies on your ability to extract information from multiple sources—research papers, reference books, different kinds of documents, fiction etc. and summarizing the findings in your own words. (p. 102)

It is important to mention that, in order to apply CLIL in EFL classes, students need to acquire literacy skills in their mother tongue (L1) first in order to be able to transfer these skills when acquiring the new language. In an educational environment such as a CLIL classroom, where language is continuously introduced, language learning is encouraged in a natural way (Wolff, 2009). Furthermore, Hüttner, Dalton-Puffer, and Smit (2013) reported that the main benefit of CLIL is using the target language in a real and meaningful way.

As mentioned before, CLIL is an approach that, aside from focusing on language teaching, highlights the teaching of curricular content subjects. Based on Banegas' (2012) definition, a content subject refers to a subject that is part of the curriculum or program and its contents are taught through and with the foreign language.

The CLIL approach "distinguish[es] certain concern with language in the subject classroom and a distinct subject pedagogy which allows the subject teacher to deploy a range of language-supportive strategies which are unfamiliar in conventional teaching" (Ball, Kelly, & Clegg, 2015, p. 19). According to the subject teachers' perceptions, neither their coverage of the content nor the students' performance (final grades) was sacrificed as a result of using English as a vehicle to convey content (Aguilar & Rodriguez, 2012).

Regarding English teaching, it is said that CLIL promotes oral communication as well as interactive skills because students are involved in discussions and active participation in class. In addition, it is reported that CLIL facilitates the learning process in all subjects (Marsh, 2002). Moreover, the use of CLIL shows that students feel motivated to participate in class using the foreign language (Pavón, Prieto, & Ávila, 2015), as they feel their English is improving using this approach (Lasagabaster & Doiz, 2016).

McDougald (2015), in his study with the Basque Community in Spain, found that teachers agreed on the fact that CLIL can be used not only with students of all age levels but also with different types of education (formal and informal settings). In addition, Dallinger, Jonkmann, Hollm, and Fiege (2015) reported that students found their content subjects more enjoyable and interesting in CLIL classes, which increased their intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Likewise, using CLIL involves developing thinking skills. In a study carried out by Bruno and Checchetti (2015) in a CLIL class, they pointed out teachers' opinions regarding two important aspects: scaffolding and taxonomy. Scaffolding helps students learn the language, and taxonomy helps students learn the content. In this endeavor, it is necessary to use different learning strategies, such as writing prompts or definitions, metalinguistic clues, peer dictation, information gap activities, visuals, or graphic organizers, which are used to endorse the achievement of Lower Order Thinking Skills (LOTS) and Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS), two levels of intellectual behavior that are important in learning and were developed by Benjamin Bloom (Kusuma, Rosidin, Abdurrahman, & Suyatna, 2017).

According to Ball, Kelly, and Clegg (2015), teachers need to train students "to use problem solving skills, to engage them interculturally, to develop their sense of initiative, and to ground them in an awareness of the ethical consequences of their actions..." (p. 32). It is important, as teachers, to assist students in improving not only their comprehension of content but also their language skill in order to help them develop thinking skills, which will be used later in life.

As regards the students' perceptions about the implementation of CLIL in their classes, some studies (Aguilar & Rodriguez, 2012; Nuñez Asomoza, 2015) agree that students had some concerns at the beginning: first, about not having native English-speaking teachers; and second, about being unable to participate in oral activities due to their own language issues. However, they later reported being satisfied with both their teachers' English proficiency and their own oral participation.

As for teachers' strategies and material used in CLIL classes, Morton (2013) stated that it is necessary not to use material designed for native speakers who are content subject students, but to develop material from scratch. In this regard, "such practices included appropriateness of language and content for learners, appropriateness for educational and cultural context, flexibility, design and pedagogic approach, and availability and convenience" (Banegas, 2016, p. 24).

It is worth mentioning that developing CLIL material makes it easier to achieve coherence, as it highlights academic subjects or learner-contributed content in a sequencing and evolving manner, and it also considers complexity. Moreover, CLIL teaching lessons and materials are expected to grow from LOTS to HOTS (Banegas, 2016). Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) have declared that, regarding the material, students found it appropriate in terms of language and content. They also reported that, after becoming familiar with the material, they became less concerned about understanding the lesson. This is an important finding because material can produce either anxiety or motivation.

Regarding evaluation, Dafouz (2007) revealed that subject teachers have not been too concerned with language issues in the assessment process, which indicates that content is their priority, probably because they do not feel prepared to assess language learning.

In this endeavor, it is imperative to motivate teachers and to make them aware of the need for more training opportunities, not only in the academic use of language but also in current methodologies and evaluation (content and language). Moreover, it is essential to have more support from institutions, as well as more coordination among teachers to become competent in content subject (Pladevall-Ballester, 2015).

Authors such as Aguilar and Rodriguez (2012), Morton (2013), and Lasagabaster and Doiz (2016) mention the importance of asking not only teachers, but also students about their opinions and perception on the implementation of these programs. In this regard, it is important to consider their awareness of self-efficacy, which could allow learners to gain "confidence in their overall ability to learn the language" (Cotterall, 1999, p. 502).

Important research studies have been conducted in this field (Dehghani, Jafari Sani, Pakmehr, & Malekz, 2011; Phan, 2009), finding a very close relationship between the development of critical thinking abilities and learners' self-efficacy in second language students. Furthermore, Fahim (2013) concluded that the students' perceptions and beliefs is what influences their motivations, attitudes and learning procedures.

Considering the above, and in an attempt to contribute with some insights that might help the improvement of foreign language teaching and EFL teaching programs, the present study analyzes the application of the CLIL approach in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca in Ecuador. Consequently, the following research questions were addressed:

» What is the students' linguistic competence in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program?

» Do students develop HOTS in the content subjects taught in English?

» What are the students' perceptions about their acquisition of language, content and HOTS through the CLIL methodology used in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program?

Method

This study is a quantitative exploratory research that provides an orientation for the researcher by gathering information on CLIL at higher education, a lesser-known topic. The researchers wanted "to investigate a cause-and-effect relationship" (Patten, 2009, p. 3) and to diagnose the different dimensions of implementing CLIL in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca. Moreover, they analyzed if students develop content knowledge, language proficiency, and HOTS simultaneously, which are the three core components of this type of methodology.

It is important to mention that through this exploratory study, we expected to obtain background information that would possibly give some insight into the current situation at this Pre-Service EFL Teaching program.

The context

The study was conducted at the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the School of Philosophy of the University of Cuenca. The program trains teachers in the process of teaching and learning English as a foreign language through the implementation of educational resources that allow students to generate processes in the classroom, helping them raise their level of competence in English in school at the different levels of education (initial, primary, secondary, and tertiary).

The main objective of the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program is for students to achieve an adequate oral and written use of the target language at a B2 level (Facultad de Filosofía de la Universidad de Cuenca, 2013), with relevant knowledge about English linguistics, as well as its literary and cultural manifestations. The program has a duration of nine semesters, the first three of which are devoted to language-only courses, such as English Grammar, Conversation, and Reading and Writing, among others. When they reach the fourth semester, students are required to take content courses (included in the curriculum), which are taught in English. These courses are Masterpieces of English Literature 1, Masterpieces of English Literature 2, History of the English Language, Contemporary Literature, History and Geography, Short Stories, An Introduction to Second Language Acquisition, Theories and Methods for Learning a Foreign Language, and Testing and Evaluation. The curriculum of the program meets one of the conditions to be considered a CLIL environment, namely including content subjects taught in the target language (Ball, Kelly, & Clegg, 2015).

Participants

The participants of this study were n=121 students from the Pre-Service EFL Teaching Program at the University of Cuenca. Data was collected over one year, distributed in two academic semesters. The only criterion to be selected as a participant of the study was to be enrolled in at least the fourth semester because, as previously mentioned, that is when students start taking content subjects.

During the first semester of 2016, which goes from March to July, data was collected from students taking content courses in the fifth and seventh semesters. During the second semester, that is, from September 2016 to February 2017, data was collected from participants taking content subjects in the fourth semester. It is important to mention that data was not taken from sixth-semester students because that information had already been collected when those participants were in their fifth semester. Additionally, data was not collected from students during the eighth and ninth semesters because the main objective in these two levels is to write their thesis proposal and to develop their thesis, respectively.

The 121 participants were mostly women (72.7%). A vast percentage (98.3%) of students were native speakers of Spanish and, similarly, most of them were Ecuadorian (97.5%). At the time of the study, 26.4% were enrolled in the fourth semester, 34.7% in the fifth, and 38.8% in the seventh.

Most of the participants (75%), mentioned they studied in an urban school, and 25% in a rural one; 70.2% studied in public schools and the remaining group in private institutions. Approximately 43.8% of the students declared they were not working at the time of the study. It is worth mentioning that, in the past, only 38% had had access to private English lessons, and 19.8% of the students had studied a language other than English. Similarly, 6.6% of the students had lived in an English-speaking country, while 8.1% had traveled abroad to study the language.

The study

This is a quantitative exploratory study in which the students at the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program of the University of Cuenca were asked to take an English placement test to measure their general proficiency in the language and help them analyze how close they were to reaching the program's requirement (B2 level). A survey on their perceptions about language, content learning, and HOTS development in their content classes in English (CLIL) was also applied to the participants. This survey was used to get insights on what students consider to be the strengths and weaknesses of the program with regard to the CLIL objectives. Finally, written assignments provided by the teachers were collected to analyze the development of HOTS.

Data collection instruments

The investigation took place during regular classes; data collection was carried out with the consent of teachers and participants, and by administering the Top Notch/Summit placement test to assess the general English proficiency of the students. This evaluation tool used was the Pearson Longman standardized test published in 2005, which contains 120 items and assesses listening, vocabulary, grammar, and social language.

A scale for HOTS development evaluation was also used. This rubric was adapted from the one used in the study Critical Thinking Rubrics and Academic Performance (Hohmann & Grillo, 2014). The HOTS development assessment was subdivided into subject assessment and assessment of skills at a general level, as well as evaluation of the students' written production. This rubric, which is graded over 100 points, considered the following aspects: (1) basic concepts and principles; (2) elaboration and evaluation; (3) written fluency and interaction; and (4) accuracy. As far as the analysis of academic writing is concerned, a sample of 58 of the students' tests and written assignments were analyzed. For doing this purpose, students had to write about a topic provided by the teacher regarding the content of the subject matter.

A survey to inquire students' perceptions about language, content learning, and HOTS development was also applied to the participants. This instrument was divided in three aspects: (1) students' perceptions on their language acquisition in the different content subjects during their studies in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca; (2) students' perceptions on their comprehension of the content in these subjects; (3) students' perception on the development of HOTS. These perceptions were evaluated with a scale from 0% (equivalent to nothing) to 100% (equivalent to all).

Confidentiality was ensured during the administration of the different tests and questionnaires by assigning numerical codes.

Results

As regards the CLIL methodology used in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program, it was analyzed according to the students' general English proficiency, the examination of academic writing assignments, the level of HOTS development, the students' perceptions of class comprehension, and a correlation between the students' English proficiency provided by the general English proficiency test, and the students' perceptions of the language skills development per subjects. It is important to highlight that no intervention took place in this study, since, as previously mentioned, it was an exploratory research that aimed to diagnose the current situation of the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca in order to take further actions, if needed.

English proficiency test results

In order to find out the students' linguistic competence level in the content subjects in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program, the results from the placement test were analyzed in the six groups of students participating in this study, two groups in each class. The groups with the highest number of students are those in the fourth and seventh groups.

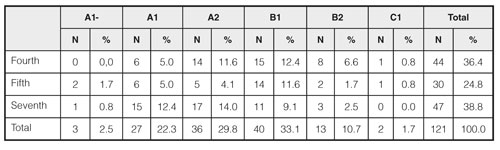

Source: Own elaboration.

From the total number of students evaluated, 22.3% are in the A1 level, 2.5% in A1-, 29.8% in A2, 33.1% in B1, 10.7% in B2, and only 1.7% are in C1. These results are not favorable for the English teaching major because both the program and the Project for Strengthening English Teaching presented by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Education (MCER) require that both pre- and in-service English teachers reach at least the B2 level of proficiency in the target language, (Ministerio de Educación, 2011). The results obtained show that the required level is only met at 10.7%, while only 1.7% is above that level.

Academic writing assessment

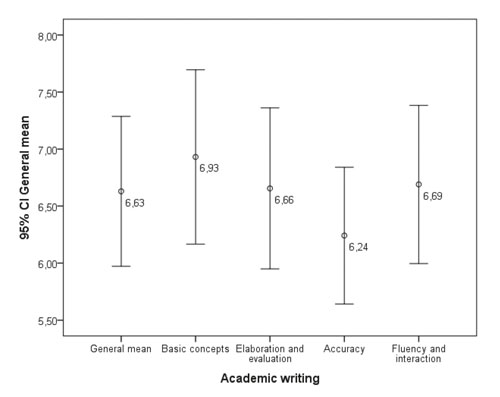

Regarding the thinking skill strategies that students develop and use in content subjects to reach the learning outcomes, the results from the students' written production analyzed by the researchers showed that there is a general average of 6.6% thinking skill strategies. This implies that there are data on the higher and lower extremes, which revealed that understanding the basic concepts reaches the highest average in the scale of thinking skill strategies; this also happens in the fluency and interaction of the written production, but, in the language feature (elaboration and accuracy), there is an overall average of around 6% thinking skill strategies. The lowest part of the error bar, below 6, indicates that some students do not meet the expectations in academic writing because, if we consider the minimum passing grade (60 points), they would be below them (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Academic writing level

Source: Own elaboration.

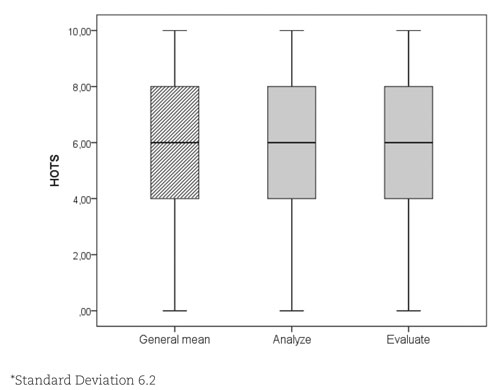

Level of HOTS development

According to the information gathered in the analysis of the development of HOTS provided by the students' written production, data showed that students are able to examine and break down information into logical pieces, identify causes and consequences, distinguish between inference and facts, and make inferences based on evidences. The results shown in Figure 2 of this evaluation revealed that data behaved similarly in the two indicators considered in the scale (analyze and evaluate) 6; the low end of the box shows values close to 4, which is "almost satisfactory." However, it should be noted that, in these two indicators of HOTS, some students had levels 0 and 2. The lower part of the box, below 6, indicates that there are students who do not meet the expectations for HOTS development because, if we match them with the minimum values to be approved in each subject (60 points), they would be below them.

Source: Own elaboration.

Students' perceptions of class comprehension

Regarding content comprehension, only 26.5% claim to understand everything from a lecture in English, and 23.5% said they understood almost everything. The two groups represent half of the total number of students. The other part is divided among those who comprehend half (20.6%), little (16.2%), and nothing (13.2 %) of the lecture. A high percentage of the students believe they learn all the content of the subject (38.3%), and only 6.2% believe they learn only half of the content; in addition, most students consider they learn almost all the content (55.6%).

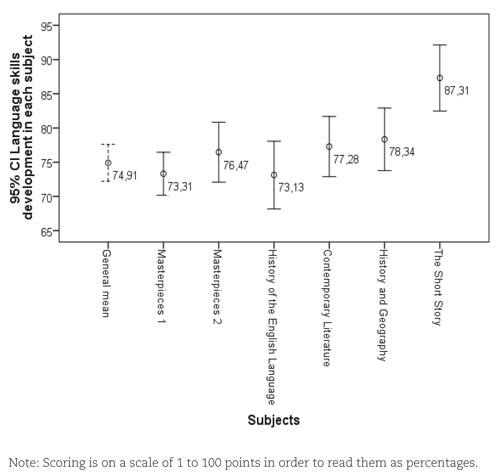

With regards to the most difficult skill, students identified speaking as number 1 (42.1%), followed by listening (39.7%) and, to a lesser extent, writing (13.2%) and reading (5%). On the other hand, students were asked about their language development in the different classes. In this regard, it was found that most students tend to present language development at half and below the maximum level—that is, around 75%, except in the Short Stories classes, which reaches the highest level (87.3%) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Perceptions of language skills development in each content subject

Source: Own elaboration.

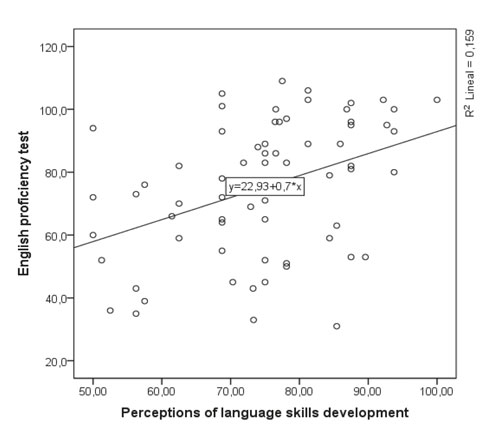

English proficiency results vs. students' perceptions of language skills development per subjects

It is imperative to mention that there is a data association with a significant correlation of 0.413, according to which those students who have higher language skills believe that they obtained higher scores in the general proficiency test. This is shown in the scatter plot diagram, where the slope shows the joint growth of the two variables and vice versa. To understand this correlation, as previously mentioned, the role that self-efficacy plays in students achieving higher levels of proficiency should be highlighted.

Figure 4. Correlation between students' perceptions of language development and the general test

Source: Own elaboration.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at University of Cuenca in light of the CLIL methodology in order to have an overview of the extent to which students are acquiring the target language and the content, as well as developing HOTS, which are dimensions developed by the effective use of CLIL. Their perceptions on their acquisition of content, language, and HOTS were also analyzed.

Therefore, according to the results yielded by the study, these students mentioned that their understanding of content and language increases in higher semesters, in contrast with the development of HOTS. This could happen because, as mentioned by Willingham (2007), thinking in a critical way depends on having enough content knowledge. It is not possible to think critically if there is not a deep knowledge that helps students recognize and execute the type of solutions needed. In this regard, there is the possibility that students in higher levels of the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca are just learning or memorizing the necessary content to pass the subject, but they are not learning it in a deep and critical way. It is divergent with the level of English of these students because only 10.7% of the evaluated students have a B2 or higher level of English according to the Common European Framework (CEFR), which does not meet the requirement that a professional should have in Ecuador to be an English teacher (Ministerio de Educación, 2011). Regarding this issue, Suesta and Renau-Ranau (2015) mentioned that one of the major difficulties for students when implementing CLIL methodologies is language use because of the specific vocabulary and expressions, as well as the necessary structures and terms to interact, explain, summarize, and solve doubts in an easier way, as needed in a CLIL class.

Another important aspect to be taken into account is the fact that many students mentioned that they learned a high percentage of the content of the subjects. This supports the findings of Aguilar and Rodriguez (2012), which state that the teaching and learning process flows regularly when using a foreign language as a teaching vehicle.

Regarding the development of thinking skills, the findings obtained from the analysis of the students' written production show that most students are developing HOTS. Nevertheless, there are a number of students who are left behind. Some causes of this delay in developing HOTS could be attributed to the fact that students were not required to either analyze, evaluate, or create in their written assignments, as evidenced in the results obtained through the HOTS assessment rubric. These results resemble those reported by Bruno and Checchetti (2015), who assert that this problem occurs because teachers are not using enough learning strategies to help students learn the content. Likewise, Ball, Kelly, and Clegg (2015) mentioned that, as teachers, we should train students to improve content comprehension and language skills and, in this way, they will develop their thinking skills.

It is important to consider the correlation found between the students' perceptions of language development and the General Proficiency Test because it may correspond to the sense of self-efficacy. As mentioned by Fahim (2013), the language learning process is usually affected by students' attitudes, motivation, and beliefs; if these aspects are not positive, they might interfere in the students' success. Therefore, in this study it was noted that students who have higher language skills believe they are those who obtained higher scores in the general test.

Some difficulties regarding academic writing were faced in this study, even though in the first three semesters of the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca, students take classes such as Conversation I, II and III, Reading Comprehension I, II, and III, Writing I and II, and two semesters of Grammar. According to Nuñez-Asomoza (2015), students claimed the need for more EFL classes in order to get a better English proficiency level. In this respect, it could be the case of the students in the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program at the University of Cuenca because the listening skills, for example, are not being considered as a course. According to some authors, it is a fundamental skill for the development of the other skills, particularly speaking (Field, 2008).

Conclusions

As indicated in the results obtained, there is a high percentage (52%) of students in levels A1- and A2. This is not a satisfactory situation, and it seems that the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program is not preparing its students in the development of language proficiency properly, and, as a consequence, students have issues when learning content courses taught in English.

Although students take EFL courses as a prerequisite to enroll in content subjects, the level of proficiency does not reach the required B1 level; as seen in the results, 54.5% of students are between levels A1-, A1, and A2. Furthermore, students also perceive that the most difficult skills are listening and speaking; therefore, it could be important for students to take listening as a course as well.

Another essential recommendation, to be considered later on, is that teachers may need to pay attention to language issues while assessing subject content because, according to Dafouz (2007), teachers have mastered content and forgotten the language; therefore, they do not feel able to assess the target language.

Regarding academic writing skills, although only a sample was evaluated, the results reflect that there are students who have an unsatisfactory level. It would then be relevant for future research to evaluate students who are starting the first semester and after they finish the third one in order to determine the factors preventing the progress in the development of the four language skills, especially writing.

According to the students' perceptions, it seems they are acquiring the necessary subject knowledge; nevertheless, language is being relegated to second position, and it is not being developed with content, simultaneously.

The results of the sample analysis showed that the development of HOTS reaches a satisfactory rate; however, there are students who are not able to examine and break information into pieces, identify causes and effects, or make inferences, which should be considered because the development of thinking skills is fundamental to learn any content subject, and it is said that it determines academic success or failure.

CLIL offers a methodology that could contribute to develop content, language, and HOTS, since these three dimensions are the basis of this approach. CLIL suggests that class planning is done by taking into consideration these three dimensions, which should be described in the syllabus as part of the learning outcomes, since both language and content are considered to be vehicles for developing HOTS.

It would be convenient to find a mechanism through which students who reach a minimum B1 level at the fourth semester can level themselves to bridge the gap between the level of content learning and the level of English proficiency.

Limitations and opportunities for further research

A clear limitation of this study that should be mentioned has to do with the placement test Top Notch/Summit, which assesses listening, vocabulary, grammar, and social language. An international standardized test such as the TOEFL would have given more effective results.

A second limitation was the fact that not all teachers at the Pre-Service EFL Teaching program collaborated actively because not all of them delivered the assignments and tests handed in by their students. Consequently, in further research it would be advisable to provide students with a test to evaluate the development of the different skills needed in the study.

References

Aguilar, M., & Rodriguez, R. (2012). Lecturer and student perception on CLIL at a Spanish university. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(2), 183-197. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2011.615906.

Ball, P., Kelly, K., & Clegg, J. (2015). Putting CLIL into practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Banegas, D. (2012). CLIL teacher development: Challenges and experiences. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 5(1), 46-56. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2012.5.1.4

Banegas, D. (2016). Teachers develop CLIL material in Argentina: A workshop. LACLIL, 8(1), 17-36. doi:10.5294/laclil.2016.9.1.2.

Bruno, M. C., & Checchetti, A. (2015). CLIL & IBSE methodologies in a chemistry learning unit. European Journal of Research and Reflection in Educational Science, 4(8), 1-12.

Cotterall, L. (1999). Key variables in language learning: What do learners believe about them? System, 27, 493-513.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge, UK: CUP.

Cummins, J. (1984). Bilingualism and special education: Issues in assessment and pedagogy. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J. (2013). Bilingual education and content and language integrated learning (CLIL). Padres y Maestros, 349, 6-10.

Dafouz, E. (2007). On content and language integrated learning in higher education. The case of university lecturers. RESLA, 1, 67-82.

Dallinger, S., Jonkmann, K., Hollm, J., & Fiege, C. (2015). The effect of content and language integrated learning on students' English and history competence - killing two birds with one stone? Learning and Instruction, 41, 23-31. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.003.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2011). Content-and-language integrated learning: From practice to principles? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 182-204. doi:10.1017/S0267190511000092.

Dehghani, M., Jafari sani, H., Pakmehr, H., & Malekzadeh, A. (2011). Relationship between students' critical thinking and self-efficacy beliefs in Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2952-2955. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.221.

Facultad de Filosofía de la Universidad de Cuenca. (2013). Plan de carrera de ciencias de la educación en la especialidad de lengua y literatura inglesa. In Universidad de Cuenca.

Retrieved from https://www.ucuenca.edu.ec/la-oferta-academica/oferta-de-grado/facultad-de-filosofia/carreras/literatura-inglesa

Fahim, M. (2013). The relationship between Iranian EFL students' self-efficacy and critical thinking ability. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(3), 538-543. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.3.538-543.

Field, J. (2008). Listening in the language classroom. Retrieved from http://ebooks.cambridge.org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9780511575945

Hohmann, J., & Grillo, M. (2014). Using critical thinking rubrics and academic performance. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 45, 35-52. doi: 10.1080/10790195.2014.949551.

Hüttner, J., Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2013). The power of beliefs: Lay theories and their influence on the implementation of CLIL programmes. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), 267-284. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2013.777385.

Kusuma, M. D., Rosidin, U., Abdurrahman, A., & Suyatna, A. (2017). The development of higher order thinking skills (HOTS) instrument assessment in physics study. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR - JRME), 7(1), 26-32.

Lasagabaster D., & Doiz, A. (2016). CLIL students' perceptions of their language learning process: Delving into self-perceived improvement and instructional preferences. Language Awareness, 25(1-2), 110-126.

Marsh, D. (2002). CLIL/EMILE - The European dimension: Actions, trends and foresight potential. Jyväskylä, Finland: University of Jyväskylä.

McDougald, J. (2015). Teachers' attitudes, perceptions and experiences in CLIL: A look at content and language. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(1) 25-11.

Ministerio de Educación. (2011, July 10). Fortalecimiento del inglés. Retrieved from https://educacion.gob.ec/objetivos-2/

Morton, T. (2013). Critically evaluating materials for CLIL: Practitioners', practices and perspectives. In J. Gray (Ed.), Critical perspectives on language teaching materials (pp. 111-136). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nuñez-Asomoza, A. (2015). Students' perceptions of the impact of CLIL in a Mexican BA program. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(2), 111-124. doi: 10.15446/profile.v17n2.47065

Patten, M. (2009). Understanding research methods. An overview of the essentials (7th ed.).Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing.

Pavón, V., Prieto, M., & Ávila, F. J. (2015). Perceptions on teachers and students of the promotion of interaction through task-based activities in CLIL. Porta Linguarum, 23, 75-91.

Phan, H. (2009). Relations between goals, self-efficacy, critical thinking and deep processing strategies: A path analysis. Educational Psychology, 29, 777-799.

Pladevall-Ballester, E. (2015). Exploring primary school CLIL Perceptions in Catalonia: Students', teachers', and parents' opinions and expectations. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 18(1), 45-49.

Prudnikova, N. N. (2016). Topicality of linguistic competence and performance teaching at higher educational institutions of the Russian Federation (on the Example of RANEPA). International Journal of English Linguistic, 6(2), 99-104. ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703.

Smit, U., & Dafouz, E. (2012). Integrating content and language in higher education: An introduction to English-medium policies, conceptual issues and research practices across Europe. AILA Review, 25, 1-12. doi: 10.1075/aila.25.01smi

Suesta, F. G., & Renau Renau, M. L. (2015). A critical vision of the CLIL approach in secondary education: A study in the Valencia community in Spain. LACLIL, 8(1), 1-12. doi:10.5294laclil2014.8.1.1.

Willingham, D. (2007). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Educator, 109(4), 8-19. doi:10.3200/AEPR.109.4.21-32

Wolff, D. (2009). Content and language Integrated learning. In K. Knapp, & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Handbook of foreign language learning and communication (pp. 545-572) Berlin, Germany: de Gruyter.