Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia.

jermaine.mcdougald@unisabana.edu.co

Editorial

Jermaine S. MCDOUGALD

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2558-5178.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2558-5178.

Universidad de La Sabana, Colombia.

jermaine.mcdougald@unisabana.edu.co

Introduction

There are many variables that must be considered when designing a curriculum, especially one that caters to language and content. A curriculum of this type helps prepare learners for real world issues. At present, many curricular programs are geared towards 21st-century skills (Deyrich & Stunnel, 2014; Görlach, 1999), but there are frequently questions about how these skills are integrated into the curriculum in such a way that importance is shared equally between content and language. Content in itself is often mistaken for subjects such as math, science, and geography but, in contrast, a language course is almost never considered content. This is because the entire educational system, not to mention that it is a systematic cultural view arising from the ideological values of modernism over the past several centuries, where the system separates the teaching and learning of language and content subjects when they should really be uniting them. Content can, after all, be defined as knowledge and/or skills that the learners would need to acquire even if they were not also learning the CLIL language (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010). In education, content is usually labeled as a "content area", which UNESCO's International Bureau of Education (2018) define as "topics, themes, beliefs, behaviors, concepts and facts, often grouped within each subject or learning area under knowledge, skills, values and attitudes, that are expected to be learned and form the basis of teaching and learning" (p. 1).

What is needed for a content and language curriculum?

Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) emphasize that there are operational factors as well as a scale to help determine the type of CLIL program that fits a particular context. The operational factors directly affect the way in which a curriculum is designed and set up; they include a) teacher availability, b) both teachers' and students' language proficiencies, c) the number of hours distributed between both L1 and L2, d) how language and content are integrated, and e) connections between the curriculum and elements outside the immediate school context.

An educational institution's context is a crucial factor for consideration when designing and implementing programs that integrate both language and content. For practical purposes, it can be argued that content and language integrated learning (CLIL) and content-based instruction (CBI) share the same essential properties (Cenoz, 2015); both are content driven and could form a practical approach to almost any given curriculum. Nevertheless, it is also true that, regardless of whether CLIL or CBI has been the basis of curricular deign, that in practice programs theoretically designed around these principals often lack any emphasis on language, despite language being necessary for learners to interact successfully with the content.

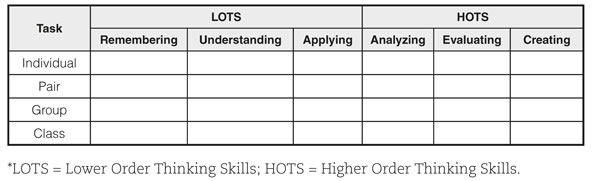

Yet CLIL (and similar approaches), if properly understood and used, should present idea ways of focusing on language as a tool to access and share content knowledge. In such ways, students are not merely exposed to the vehicular language, they also have opportunities to think in in the L2 and produce meaningful content in the L2, supporting more rapid and practical acquisition of their L2 skills in general. The beauty of working with a CLIL-oriented curriculum is that language, content, and cognition can all be linked together. But to address the challenges that teachers and administrators may have in transforming the theory into practice, tools such as a CLIL planning matrix (Figure 1), based on Cummins' quadrant model (Cummins, 1989, 2000; Halbach, 2012; Khatib & Taie, 2016), can help distribute focuses on Basic Interpersonal Communication skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic language Proficiency (CALP) more evenly throughout the curriculum. Such a matrix can help practitioners consider how to include both higher- and lower-order thinking skills (HOTS and LOTS) into their lessons.

Figure 1: Matrix: task design.

Source: Own elaboration.

Factors to consider for curriculum

Educators have long used different curricular models in different contexts to achieve CLIL objectives. Yet such objectives cannot be achieved overnight; institutions need to plan for short, medium, and long-term goals associated with curricular changes. Careful planning in terms of understanding the context at hand, supporting team work, and providing ample feedback on implementation processes are essential for successful CLIL curriculum planning. Feedback can be provided in numerous way, including through classroom observations, periodic meetings with stakeholders, and focus groups (Coyle et al., 2010; Jarson, 2010; Meyer, Coyle, Halbach, Schuck, & Ting, 2015; Vázquez & Gaustad, 2013).

CLIL team teaching and communication

Even in cases where other design factors have been considered, the issue of what kind of personnel are needed to form a CLIL teaching team is often left out. This can contribute to breakdowns in communication processes within the given educational institution, thereby leading to the generation of misinformation, lack of attention, and the creation of isolated initiatives. Putting together a CLIL curriculum requires a coordinated and unified effort amongst all the involved personnel. Issues that must be considered in concert include the number of hours to be taught in the vehicular language, teacher profiles, subjects to be taught, and evaluation and assessment practices. Design and implementation teams be constituted coherently, with periodic meetings in which responsibilities can be assigned and plans put into place. Such teams are ultimately responsible for issues such as language management, language education, and language and content integration.

Changes in education

As mentioned earlier, educational systems world-wide need to change the way education is structured to train students with the competencies to respond to the demands of a more interconnected and knowledge-driven world. Educators need to revolutionize themselves, modernizing educational institutions prepare learners for social, professional, and civic environments that are in many ways very different from those that contemporary educational systems were originally designed to meet. This educational revolution is at large a widespread change so that all stakeholders involved become active participants in making these changes come to light. (Robinson, 2001, 2011; Robinson & Aronica, 2009; Robinson, Minkin, & Bolton, 1999)

Research conducted with the employers indicates that, even in the most developed countries, universities no longer equip students to respond to the new, changed requirements to be placed in the contemporary jobs (Popovic, 2014). Changes to education also need "to incorporate new teaching and/or learning approaches that enable the development of critical and creative thinking skills"(Granados, 2018, p. 5). Such 'new' educational programs should also try to accelerate the pace of relevant learning, as well directly relating teaching and learning process through curricular items to prepare students for real-life situations. In response to such needs, and/or as a result of educational/curricular reform, many institutions are starting to opt for CLIL/CBI-based approaches, where improvements can be made in learners' L2 fluency, as they are actually using language in practical ways, derived from the situation of content in context. (Pinner, 2013). Such situations not only encourage students to use academic language but also content-specific vocabulary autonomously, authentically, and for real purposes.

One advantage of a CLIL-oriented curriculum is that it can be implemented to start with through just two or three subjects, helping learners begin to become accustomed with the processes of internalizing knowledge acquired through the vehicular language, whether first through math, science, social studies, or content-based language arts (i.e. literature and other "content-based" areas frequently associated with language knowledge and use). In any event, learners are need to be able to master both language and content-based knowledge (such as mathematics); their integration help them become more natural parts of students' real lives as they continue to interacting within their communities or wider society. The effective integration of content and language within the curriculum thus supports a range of both more and less obvious benefits to learning and learners, as they are able to use the content acquired in the target language immediately for real, authentic purposes, and to think in the new vehicular language, naturally combining HOTS and LOTS, BICS and CALP in both academic and non-academic environments (Anderson, 2011; Várkuti, 2010; Khatib & Taie, 2016).

In this issue

The articles in this issue of the Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning (LACLIL, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2018) are focused on the different ways in which CLIL is being used across the curriculum. This issue begins with a systematic literature review on the effects of Content-Based Instruction (CBI) and CLIL on language and content outcomes (Graham, Choi, Davoodi, Shakiba, & Dixon, 2018). The results from comparing twenty-five selected articles show that previous studies have revealed both positive and neutral effects on language and content outcomes in both CBI and non-CBI environments. However, the authors also found multiple issues related to the different types of methodologies being used in the evaluated studies, making it difficult to build a case for the positive effects of the CBI programs—at least as designed and implemented. Reviews of this kind provide important contributions to the field of content and language integration, as there is still a lack of research-based evidence on how CBI, CLIL, or EMI approaches are really working. The present study suggests a gap between theory and practice that CLIL educators need to address.

Bellés-Calvera (2018) discusses a CLIL approach being tested in a music program delivered through an L2 (English, in this case) to a group of high-school students in Spain. The results revealed that the participants enjoyed music lessons in the vehicular language, especially when audio-visual aids were incorporated, with increased levels of motivation, and the authors concludes that it would be feasible to expand the implementation of such classes.

Argudo, Abad, Fajardo-Dack, and Cabrera (2018) analyze whether a CLIL approach would be beneficial for an undergraduate university EFL program in Ecuador, observing 121 students across three semesters. Their study evaluated the students' higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) as well as their perceptions regarding the development of language and content knowledge and skills. The results indicated that the participants did not have the necessary linguistic background complete the existing content courses taught in the additional language, but also that the professors were not planning for a CLIL approach that integrated the three dimensions of content, language, and cognition— with the result that participants were not simultaneously developing these dimensions, as could perhaps be better supported through a consciously planned CLIL-based curriculum.

Along the same lines, Reitbauer, Fürstenberg, Kletzenbauer, and Marko (2018) examine how cognition is handled in an Austrian classroom, evaluating a framework for strengthening the integration of content and language. Their findings suggest that the role of language, as it is related to knowledge building, needs more emphasis and consideration from CLIL practitioners in "hard" CLIL scenarios. They also claim that teachers needed to improve their own language awareness, which in turn would help them understand how to reduce the cognitive load in these types of classes.

Alcaraz-Mármol (2018) studied 60 in-service primary school educators towards CLIL, comparing and contrasting the attitudes of teachers who had either received CLIL training or who had not. The results reveal several clear differences, in particular that the CLIL-trained teachers included more diverse resources and activities in their classes while the teachers without CLIL training had less variety. Accordingly, the authors suggest that CLIL training should be mandatory and highlight that ELT professionals would benefit from standard CLIL training that is no less comprehensive that the linguistic and pedagogical training that they already receive.

Finally, Sarasa, and Porta (2018) explore the co-construction of teaching identities narrated by 24 undergraduate students in an ELT pre-service education program in Argentina. The authors studied the lived experiences of the participants involving aspects such as love, desire, imagination, and fluidity. Their results helped these pre-service teachers understand the implications of research in initial university teaching programs.

Overall, the articles in present issue of the Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning (LACLIL, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2018) provide insights into the different ways that content and language curricula interact with the classroom, as well as "food for thought" on the extent to which the learning of content in CLIL environments is genuinely taking place. The authors in this issue leave us with questions regarding the current state of content and language integration, whether founded on CLIL, CBI, or EMI approaches. To be sure, although such methods and approaches are broadly intended to lead to the same kinds of end results—increased content knowledge and higher levels of cognition— it nevertheless seems safe to say that more research in these areas— in language and learning outcomes, specifically planned and organized through a new curriculum that equally contemplates language and content—is needed.

References

Alcaraz-Mármol, G. (2018). Trained and non-trained language teachers on CLIL methodology: Teachers' facts and opinions about the CLIL approach in the primary education context in Spain. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 39-64. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.3

Anderson, C. E. (2011). CLIL for CALP in the multilingual, pluricultural, globalized knowledge society: Experiences and backgrounds to L2 English usage among Latin American L1 Spanish-users. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning, 4(2), 51-66. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2011.4.2.5

Argudo, J., Abad, M., Fajardo-Dack, T., & Cabrera, P. (2018). Analyzing a pre-service EFL program through the lenses of the CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) approach at Universidad de Cuenca, Ecuador. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 65-86. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.4

Bellés-Calvera, L. (2018). Teaching Music in English: A Content-Based Instruction Model in Secondary Education. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 109-139. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.6

Cenoz, J. (2015). Content-based instruction and content and language integrated learning: the same or different? Language, Culture and Curriculum. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2014.1000922

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cummins, J. (1989). Theoretical Background. TESOL Quarterly Article Stable URL. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27526-5_2

Cummins, J. (2000). Chapter 3. Language proficiency in academic contexts. In C. Baker, & N. Hornberger (eds.), Language, Power and Pedagogy. Bilingual Children in the Crossfire (pp. 57-85). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Deyrich, M. C., & Stunnel, K. (2014). Language teacher education models: New issues and challenges. Utrecht Studies in Language & Communication, 27, 83-105.

Retreived from https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-3296855931/language-teacher-education-mod-els-new-issues-and

Görlach, M. (1999). David Graddol, <I>The Future of English? A Guide to Forecasting the Popularity of the English Language in the 21st Century</I>. English World-Wide. 10.1075/eww.20.1.11gor

Graham, K. M., Choi, Y., Davoodi, A., Shakiba, R., & Dixon, L. Q. (2018). Language and content outcomes of CLIL and EMI: a systematic review. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 19-37. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.2

Granados, J. (2018). The Challenges of Higher Education in the 21st Century. Retrieved September 1, 2018,

from http://www.guninetwork.org/articles/challenges-higher-education-21st-century

Halbach, A. (2012). Questions about basic interpersonal communication skills and cognitive language proficiency. Applied Linguistics. doi: 10.1093/applin/ams058

Jarson, J. (2010). Information literacy and higher education: A toolkit for curricular integration. College & Research Libraries News, 71(10), 534-538.

Khatib, M., & Taie, M. (2016). BICS and CALP: Implications for SLA. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 7(2), 382. doi: 10.17507/jltr.0702.19

Meyer, O., Coyle, D., Halbach, A., Schuck, K., & Ting, T. (2015). A pluriliteracies approach to content and language integrated learning-Mapping learner progressions in knowledge construction and meaning-making. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 28(1). doi: 10.1080/07908318.2014.1000924

Pinner, R. (2013). Authenticity and CLIL: Examining Authenticity from an International CLIL Perspective. International CLIL Research Journal.

Popovic, D. (2014). Guest editor's introduction: The challenges students are facing in the 21st century. Singidunum Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 1-4.

Reitbauer, M., Fürstenberg, U., Kletzenbauer, P., & Marko, K. (2018). Towards a cognitive-linguistic turn in CLIL: unfolding integration. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(1), 87-107. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.5

Robinson, K. (2001). Mind the gap: The creative conundrum. Critical Quarterly, 43(1), 41-15. doi: 10.1111/1467-8705.00335

Robinson, K. (2011). Out of our minds: Learning to be creative (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Capstone/John Wiley & Sons.

Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/Out-Our-Minds-Learning-Creative-ebook/dp/B005CK-KETU/

Robinson, K., & Aronica, L. (2009). The element: How finding your passion changes everything. London, UK: Allen Lane.

Robinson, K., Minkin, L., & Bolton, E. (1999). All Our Futures : Creativity, Culture and Education. National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education. doi: 10.1075/prag.22.3.02gre

Sarasa, M. C., & Porta, L. G. (2018). Narratives of desire, love, imagination, and fluidity: becoming an English teacher in a university preparation program. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(11), 141-163. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.7

UNESCO. (2018). Internacional Bureau of Education. Available from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/ibe-alert/12-july-2018

Várkuti, A. (2010). Linguistic Benefits of the CLIL Approach: Measuring Linguistic Competences. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(3), 67-79.

Available from http://www.icrj.eu/13/article7.html

Vázquez, V. P., & Gaustad, M. (2013). Designing Bilingual Programmes for Higher Education in Spain : Organisational , Curricular and Methodological Decisions, 2(1), 82-94.